More

Certified fresh picks

New TV Tonight

-

Dark Winds: Season 4

100% -

56 Days: Season 1

63% -

Like Water for Chocolate: Season 2

-- -

The Night Agent: Season 3

-- -

The Last Thing He Told Me: Season 2

-- -

Strip Law: Season 1

-- -

Dreaming Whilst Black: Season 2

-- -

Being Gordon Ramsay: Season 1

-- -

Shoresy: Season 5

-- -

Portobello: Season 1

--

Most Popular TV on RT

-

A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms: Season 1

94% -

Naked and Afraid: Season 19

-- -

The Artful Dodger: Season 2

100% -

How to Get to Heaven From Belfast: Season 1

91% -

Unfamiliar: Season 1

-- -

Dark Winds: Season 4

100% -

Tell Me Lies: Season 3

-- -

Drops of God: Season 2

91% -

His & Hers: Season 1

69%

More

Certified fresh pick

Columns

Guides

-

RT Recommends: Our Favorite Movies This Week

Link to RT Recommends: Our Favorite Movies This Week -

Best New Movies of 2026, Ranked by Tomatometer

Link to Best New Movies of 2026, Ranked by Tomatometer

Hubs

-

What to Watch: In Theaters and On Streaming

Link to What to Watch: In Theaters and On Streaming -

Awards Tour

Link to Awards Tour

RT News

-

The Devil Wears Prada 2: Release Date, Cast, Trailers & More

Link to The Devil Wears Prada 2: Release Date, Cast, Trailers & More -

Weekend Box Office: Wuthering Heights Smolders Its Way to a $35 Million Debut

Link to Weekend Box Office: Wuthering Heights Smolders Its Way to a $35 Million Debut

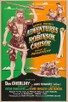

Robinson Crusoe

Where to Watch

Robinson Crusoe

Watch Robinson Crusoe with a subscription on Prime Video.

Critics Reviews

Audience Reviews

My Rating

Cast & Crew

Photos

Robinson Crusoe

Movie Info

-

Director -

Luis Buñuel -

Producer -

Oscar Dancigers , Henry F. Ehrlich -

Distributor -

United Artists -

Production Co -

Oscar Dancigers Production -

Genre -

Adventure -

Original Language -

English -

Release Date (Theaters) -

Aug 5, 1954, Original -

Release Date (Streaming) -

Aug 25, 2018 -

Runtime -

1h 30m

Continue with Google

Continue with Google

>

>